Wednesday, November 21, 2018

Sunday, September 23, 2018

Fallen Gods Update #8: Violence

Wounded and weary, a young man sits beside his battered axe and shield. All about are fallen friends and foes who, unlike this youth, have lost their lives but kept their hope. His empty, guilty hands hold no gold to atone the dead and end this gruesome feud, and his doom resounds as if the Nine sang here aloud: blood begetting blood, kith upon kin, a red wave washing away all those bound by love, oath, and wrath to war until the end. He stares at you, shaking, speechlessly beseeching.

I want you to imagine a world in which meeting your brother’s murderer on the road is sufficiently likely that a wise man might pause in his practical advice to give you suggestions as to how to handle such an encounter. That’s how the Hávamál, a kind of Norse Ecclesiastes, goes, and the suggestion (reasonable enough) is not to trust such a man-slayer. To the Hávamál’s skald, such a danger is no more or less worth warning about than rootless trees (which might tip over in a wind) or too much drink (which could lead to public embarrassment). A man should not trust in any of these, the poem warns. Everywhere is man against man, man against nature, and man against himself, and death hovers above all things like a hungry raven.

When reading the Norse sagas, what stands out to me about the violence is not so much its quantity—which is much less than in the Iliad, for instance—but its quality. The variety and specificity of wounds, along with knowledge of their consequences and the ways of trying to treat them, bespeak the skalds’ firsthand or at least secondhand experience with killing and maiming. We often think of modernity as violent, but in truth most of us will have the good fortune never to be caught up in the kind of bloodshed these sagas describe: battles, burnings, and butchery. The sagas’ authors, particularly whatever skald composed Njal’s Saga, are by no means desensitized to this mayhem. This is not the proverbial water in which a fish swims, blissfully unaware; it seems more like water in which the author is drowning, fully and fearfully conscious. A whole nation can be dragged down by such bloodshed: “by lawlessness, laid waste.”

This image of men sinking into a bloody mire of their own making has been a key part of my own writing and design for Fallen Gods.

Like many kids drawn to fantastical settings, I grew up taking comfort in the way fantasy situates violence within a moral plan. Fantasy novels are chock-full of bullied young protagonists, last survivors of near-universal slaughter, and heroes who seem helpless and hopeless against villainous might. This suffering is not just a preamble to, but a prerequisite for, later salvation. It is not merely that the wicked are punished and victims avenged; those who have been wronged find themselves, Job-like, even richer than before. (As a boy, I entirely believed that, say, Luke Skywalker could somehow be more than compensated for the trauma of coming home to the still-smoldering corpses of his murdered family. But it turns out that old wounds only ache worse as the years go on, and there is no psychic currency with which early losses can be offset by later gains.)

In typical fantasy novels, when a villain tortures a brave young woman or torches a helpless town, the bitter herb of his evil is mixed with the sweet confidence that he is merely sowing the wind. Even in ostensibly “grim-dark” series such as A Song of Ice and Fire, the long arc of history bends in favor of “breakers of chains” and once-bullied bastards. I mentioned earlier that “the noblest aspect of fantasy” is “its ability to train us to view doing good as the proper exercise of power.” Here I’ll add that its capacity to comfort, even if a kind of deceptive opiate, is no small virtue either. Run-of-the-mill childhood bullying is hardly the worst thing in the world, but it’s still rough, and that roughness is at least a bit diminished by books like The Once and Future King or any of a thousand other stories. But here, too, our game offers something different.

Unlike such fantasies, neither Fallen Gods nor the sagas that inspire it promises a moral plan for violence. When the strong use their might to hurt the weak, that does not necessarily set in motion a Rube Goldberg device by which the aggressors will ultimately suffer a comeuppance at the hands of their victims. The bloody slaughter of a people does not imply that the lone survivor will one day become king over a just, prosperous, and fecund realm; he may simply wind up an outlawed murderer meting out a measure of revenge until the day he’s caught and killed. Or he might not even make it that far. Perhaps, weak and weary, he’ll be run down a few days later and speared where he sleeps.

Our game’s setting is a world already whirling in the cyclone of such violence, and its story is that of a powerful, selfish fighter who sees others merely as a means to an end (or, we might say, a means not to end). To tell that story in that world means not flinching back from its ugliness—one must heed the cry of Aldonza in The Man of La Mancha when she is at last pushed to the brink by Don Quixote’s refusal to see the fullness of her suffering: “Won’t you look at me, look at me, / God, won’t you look at me!” As in the sagas, violence in Fallen Gods knows few limits, and it falls on the weak and undeserving no less than on the mightily wicked. Their suffering deserves to be seen and told.

That’s not to say that Fallen Gods features nothing but ugly violence or that its depictions of violence are especially gory or torturous. By the standards of modern video games and or R-rated movies, the violence is sparing and its depiction is restrained. But it is designed to have a bit more heft.

As with other aspects of Fallen Gods, that heft is conveyed mechanically. Because HP are so limited (typically single digit, even for a powerful warrior), every wound is serious. Healing is painstaking—in the field, resting restores a single HP per day, and time is valuable. There are no healing potions; rapid recovery can be achieved only by the godly skill of Healing Hands, which costs precious soul-strength, a resource the god gains only with difficulty, as previously discussed. Sickness (which encompasses both poison and disease) causes a person to grow weaker, rather than healthier, with each passing day, and unless you are strong enough to outlast the ailment, only Healing Hands or a priest’s craft can help. So too with crippling, a condition that halves the might of the injured, leaving him or her vulnerable in combat and much less helpful in events.

The seriousness of violence is also conveyed visually. Our attack and death animations avoid majestic or balletic movements. Though blood and gore is minimal, blows are meant to convey force; we want the player to wince when he sees a churl club a wolf’s skull. Illustrations likewise show battle not as glorious but in its rough-and-tumble grit.

Finally, Fallen Gods uses its narrative to drive this point home. The vignettes told through events involve not only battles in which the god participates, but also the aftermath of battles he’s missed, the weary despair that comes from the anticipation of battles that have not yet materialized, the economic drain of feuds, and so on. These events rely in part on the differences in perspective among the god (who is largely oblivious to others’ suffering), the narrator (who is aware of that suffering but takes it as a fact of life), and the player (whose values are likely very different from either the god’s or the narrator’s). The parallax effect of these overlapping perspectives is meant to be disconcerting and in some instances even dizzying, as when the narrator grumbles about surly thralls going about “unbeaten by their betters.”

Fallen Gods is an adventure in which the player has the opportunity to slay foul creatures, wield magical weapons, win powerful allies, and earn the admiration of many. But it is not unalloyed heroic fantasy, for beneath and within this quest is a frank and cautionary look at the uglier side of a world in which meting out death is viable way of life and perhaps the only way back to the heavens.

* * *

To my taste, Cormac McCarthy is the best modern skald of violence and its awful price, and his most compelling work in this regard is Blood Meridian. In a similar vein are Brian Hart’s The Bully of Order, Ian McGuire’s The North Water, Philipp Meyer’s The Son, which is probably the least agonizing of the bunch.

I want you to imagine a world in which meeting your brother’s murderer on the road is sufficiently likely that a wise man might pause in his practical advice to give you suggestions as to how to handle such an encounter. That’s how the Hávamál, a kind of Norse Ecclesiastes, goes, and the suggestion (reasonable enough) is not to trust such a man-slayer. To the Hávamál’s skald, such a danger is no more or less worth warning about than rootless trees (which might tip over in a wind) or too much drink (which could lead to public embarrassment). A man should not trust in any of these, the poem warns. Everywhere is man against man, man against nature, and man against himself, and death hovers above all things like a hungry raven.

When reading the Norse sagas, what stands out to me about the violence is not so much its quantity—which is much less than in the Iliad, for instance—but its quality. The variety and specificity of wounds, along with knowledge of their consequences and the ways of trying to treat them, bespeak the skalds’ firsthand or at least secondhand experience with killing and maiming. We often think of modernity as violent, but in truth most of us will have the good fortune never to be caught up in the kind of bloodshed these sagas describe: battles, burnings, and butchery. The sagas’ authors, particularly whatever skald composed Njal’s Saga, are by no means desensitized to this mayhem. This is not the proverbial water in which a fish swims, blissfully unaware; it seems more like water in which the author is drowning, fully and fearfully conscious. A whole nation can be dragged down by such bloodshed: “by lawlessness, laid waste.”

This image of men sinking into a bloody mire of their own making has been a key part of my own writing and design for Fallen Gods.

Like many kids drawn to fantastical settings, I grew up taking comfort in the way fantasy situates violence within a moral plan. Fantasy novels are chock-full of bullied young protagonists, last survivors of near-universal slaughter, and heroes who seem helpless and hopeless against villainous might. This suffering is not just a preamble to, but a prerequisite for, later salvation. It is not merely that the wicked are punished and victims avenged; those who have been wronged find themselves, Job-like, even richer than before. (As a boy, I entirely believed that, say, Luke Skywalker could somehow be more than compensated for the trauma of coming home to the still-smoldering corpses of his murdered family. But it turns out that old wounds only ache worse as the years go on, and there is no psychic currency with which early losses can be offset by later gains.)

In typical fantasy novels, when a villain tortures a brave young woman or torches a helpless town, the bitter herb of his evil is mixed with the sweet confidence that he is merely sowing the wind. Even in ostensibly “grim-dark” series such as A Song of Ice and Fire, the long arc of history bends in favor of “breakers of chains” and once-bullied bastards. I mentioned earlier that “the noblest aspect of fantasy” is “its ability to train us to view doing good as the proper exercise of power.” Here I’ll add that its capacity to comfort, even if a kind of deceptive opiate, is no small virtue either. Run-of-the-mill childhood bullying is hardly the worst thing in the world, but it’s still rough, and that roughness is at least a bit diminished by books like The Once and Future King or any of a thousand other stories. But here, too, our game offers something different.

Unlike such fantasies, neither Fallen Gods nor the sagas that inspire it promises a moral plan for violence. When the strong use their might to hurt the weak, that does not necessarily set in motion a Rube Goldberg device by which the aggressors will ultimately suffer a comeuppance at the hands of their victims. The bloody slaughter of a people does not imply that the lone survivor will one day become king over a just, prosperous, and fecund realm; he may simply wind up an outlawed murderer meting out a measure of revenge until the day he’s caught and killed. Or he might not even make it that far. Perhaps, weak and weary, he’ll be run down a few days later and speared where he sleeps.

Our game’s setting is a world already whirling in the cyclone of such violence, and its story is that of a powerful, selfish fighter who sees others merely as a means to an end (or, we might say, a means not to end). To tell that story in that world means not flinching back from its ugliness—one must heed the cry of Aldonza in The Man of La Mancha when she is at last pushed to the brink by Don Quixote’s refusal to see the fullness of her suffering: “Won’t you look at me, look at me, / God, won’t you look at me!” As in the sagas, violence in Fallen Gods knows few limits, and it falls on the weak and undeserving no less than on the mightily wicked. Their suffering deserves to be seen and told.

That’s not to say that Fallen Gods features nothing but ugly violence or that its depictions of violence are especially gory or torturous. By the standards of modern video games and or R-rated movies, the violence is sparing and its depiction is restrained. But it is designed to have a bit more heft.

As with other aspects of Fallen Gods, that heft is conveyed mechanically. Because HP are so limited (typically single digit, even for a powerful warrior), every wound is serious. Healing is painstaking—in the field, resting restores a single HP per day, and time is valuable. There are no healing potions; rapid recovery can be achieved only by the godly skill of Healing Hands, which costs precious soul-strength, a resource the god gains only with difficulty, as previously discussed. Sickness (which encompasses both poison and disease) causes a person to grow weaker, rather than healthier, with each passing day, and unless you are strong enough to outlast the ailment, only Healing Hands or a priest’s craft can help. So too with crippling, a condition that halves the might of the injured, leaving him or her vulnerable in combat and much less helpful in events.

The seriousness of violence is also conveyed visually. Our attack and death animations avoid majestic or balletic movements. Though blood and gore is minimal, blows are meant to convey force; we want the player to wince when he sees a churl club a wolf’s skull. Illustrations likewise show battle not as glorious but in its rough-and-tumble grit.

Finally, Fallen Gods uses its narrative to drive this point home. The vignettes told through events involve not only battles in which the god participates, but also the aftermath of battles he’s missed, the weary despair that comes from the anticipation of battles that have not yet materialized, the economic drain of feuds, and so on. These events rely in part on the differences in perspective among the god (who is largely oblivious to others’ suffering), the narrator (who is aware of that suffering but takes it as a fact of life), and the player (whose values are likely very different from either the god’s or the narrator’s). The parallax effect of these overlapping perspectives is meant to be disconcerting and in some instances even dizzying, as when the narrator grumbles about surly thralls going about “unbeaten by their betters.”

* * *

To my taste, Cormac McCarthy is the best modern skald of violence and its awful price, and his most compelling work in this regard is Blood Meridian. In a similar vein are Brian Hart’s The Bully of Order, Ian McGuire’s The North Water, Philipp Meyer’s The Son, which is probably the least agonizing of the bunch.

Saturday, August 18, 2018

Fallen Gods Update #7: Followers

A troll of a man, with a rumbling roar to match, calls you out before the whole hall. “Wrestle with me, little god!” he growls, clearing a ring with a sweep of his arm. The clatter and chatter stop at once, and all eyes look to you and your scornful foe. “Let me come to grips with the great might of my skyborn lord.” His smirking lips speak just as loudly as his words, and the crowd can see how little he thinks of your kind.

A major part of Fallen Gods is winning men and women to your side in your struggle to clamber back to the Cloudlands. While few mortals are a match for a god, having their help means that you will not need to fight your foes alone, and their skills may mean the difference between overcoming an obstacle and being stymied in your quest.

These “followers,” who together compose the god’s “warband,” are important thematically as well. While Norse sagas often focus on a single heroic figure, that hero is frequently defined by his relationship to his friends, family, and dependents. Thus, at the very outset, Beowulf’s skald tells us a young prince must “give[] freely while his father lives / so that afterwards in age when fighting starts / steadfast companions will stand beside him / and hold the line.” (Heaney Trans.) Interestingly, Beowulf ends with most of the king’s men running away from him, breaking the line, in his battle against the dragon. But even then, it is both thematically and tactically necessary for young Wiglaf to be there at his side to soften up the great dragon for Beowulf’s killing stroke.

There are sagas in which the protagonist is alone, but this is typically an abysmal and unusual situation—for instance, a consequence of being outlawed and cut off from human society, as in Grettir’s Saga or Egil’s Saga. The ordinary structure of these stories, reflecting the structure of the society from which they arose, is that a hero may outstrip other men and women, but he benefits from their wisdom, their rebukes, their shields, and ultimately their companionship. And from a narrative standpoint, they offer a chance for the hero to show his strengths and weaknesses in how he heeds or ignores that wisdom, bows to or refutes those rebukes, stirs or shakes the fighters who hold those shields, and wins or loses the hearts of those companions.

So too in Fallen Gods. Unlike many RPGs that make companions’ own goals, undertakings, personalities, and problems the focus of the narrative, Fallen Gods remains tightly focused on its titular protagonist. But unlike RPGs where companions are absolute non-entities, or where the hero has no companions at all, Fallen Gods uses followers as a means of enriching the god’s character and enhancing the player’s options. They will offer suggestions and reactions during events, and the player will be able to ask them to undertake tasks suited to their special skills. While followers do not have individual personalities, their sharply distinct classes (churls, woodsmen, fighters, priests, berserks, skalds, maidens, and witches) make them stand out from each other narratively, while also offering different strategic benefits at different costs.

Before going into detail about each class, it may be helpful to provide a framework for what kind of costs and benefits followers may present.

First, a follower must be located and persuaded to join the warband. Traveling to a location where the follower can be found (like a shrine or stronghold) can take days, and time is the player’s only irreplaceable resource. Once the player reaches the necessary location, the follower must be recruited. Some followers, like churls, will ask nothing; others, like fighters, will want gold; and yet others, like witches, will demand a much higher price.

Except for those that are “sworn,” a rare minority, followers must be kept happy or they will leave the warband. This requires feeding them every day; hunger eats the bonds of loyalty. Food costs either gold (if bought in town) or time (if gotten by hunting). The more followers you have (the warband can include up to five), the more food you need. Followers will also grow unhappy (and weakened) by status ailments such as being crippled (which halves might), cursed (which harms luck), or sick (which drains HP).

But even a healthy, well-fed follower will grow unhappy if the god errs. Few are fond of a god who flees or fails. And even success can be a matter of taste—the same wise restraint that impresses a priest may disgust a berserk, for instance. The player can gladden (and sometimes strengthen) a follower with the gift of an item, whether a lesser thing like a golden arm-ring or a great treasure such as Firebrand. But a gifted item is gone for good; the god can never get it back. Rest or a skald’s song can sometimes soothe the warband’s spirits, but the day thus lost cannot be regained, either.

Assuming the player can find and keep a warband, however, he gains an important edge inside and outside of combat. In battle, even a powerful god can be overwhelmed when faced with multiple foes. Followers are necessary to even the odds and prevent the god from being flanked or surrounded. And some followers, such as berserks, can do much more than merely soak up blows that would otherwise land upon the god: they can deal out death as well as their leader. Moreover, certain followers can help against certain types of foes (such as woodsmen against wolves) given their knowledge and skill.

Outside of battle, followers’ might and craft can provide the god with both generic benefits (such as the ability of a skald to raise morale, mentioned above) and special options inside of events. While events focus primarily on the god, his skills, and his choices, followers open paths in the choose-your-adventure-style events that otherwise would be unavailable—a maiden might be traded for a wurm’s wisdom; a witch might swindle dead men of their strength; a berserk might hoist a boulder too heavy for the god to lift; a priest might offer an old law to put a bitter feud to rest.

In these ways, assembling a warband is both fun in itself and a critical strategic layer of the game. The player’s job is to plot a path to victory and decide what costs can (and must) be borne to make that path possible. To be sure, luck and experience both have a role to play alongside pure reason, but there is no single combination necessary for victory: Fallen Gods is about exploration, and the dynamics and possibilities unlocked by different followers is one of the things the player is encouraged to explore.

With that framework in mind, and without further ado, here are the eight classes of followers in Fallen Gods.

Churls

To watch two churls bicker and barter over a barrow full of food is worth a laugh, but your man has a low cunning that shows itself fit for such work. In the end, he brings you much more food than you ever would have won for your gold. This is as good a deed as he can hope to do on behalf of a god, and he beams with pride when you nod in thanks.

Modern English reflects the scorn that aristocratic speakers had for those who work the land: “villain,” “churl,” “boor,” and other words that once simply meant farmer or herder are retained now in a purely pejorative sense. Notwithstanding Sir Walter Scott’s clever observation about post-1066 England in which Anglo-Saxon was the language of the field and French the language of the feast, it turns out that most of our words for one who works the land are French (like “farmer” or “peasant” or “villager”). “Yeoman” did not have a fieldworker meaning until late in its life, and is too positive for the role occupied by farmers in our setting. Hence, we are left with “churl” (from ceorl), a word that fits the low esteem the fallen god has for this class of follower.

Because churls are men who live by dint of their hard work in the fields, they are sturdy enough folk. But they lack the gear or training of a fighter, and the narrow horizons of a farmer’s life mean that they are prone to fears and superstitions. To some degree, this benefits the god: churls can be recruited for free because they are so flattered to have a god’s attention. Thus, for a player looking merely for followers to stand in the line and support the god in battle (with unskilled blows from wooden clubs), churls are a cheap and easy option. They can be found in any of the three types of steadings (plains, forest, hills) or in towns.

But beyond filling out the warband, churls don’t do much. They have no special skills, and thus are seldom helpful in opening new paths in events. In battle, they can stand and fight, but many foes will make short work of them. And while they will freely join, they eat just as much as any other follower and thus are not without their cost. A god who leads only churls may find some strength in numbers, but he is unlikely to win his way back home.

Woodsmen

The woodsman hurries on his way, swift but silent as he stalks the deer. The woods hush in his wake, and no wind stirs the leaves on which he left his tracks. When he’s been gone for far too long, you take the same path and find him at its end, wordlessly staring at what he’s done. This is a kill such as all hunters crave, a last great beast bested in its home. And yet, he seems less glad than grim as he cleans the meat for your stock, and he takes no keepsake from its corpse.

Woodsmen are perhaps of even lower class than churls because they live on the outskirts of civilization, clad in skins, hunting and foraging like forest animals. In the world of Fallen Gods, there is deep fear of humans backsliding into a pre-civilized state, one associated with the Firstborn gods overthrown by Orm. Woodsmen are close enough to that line that, despite generally being decent and somewhat gentle beings, they are not wholly welcome outside of their own forest villages.

Nevertheless, they have several skills that make them highly desirable followers. First, their pathfinding ability ensures that a god with a woodsman in his warband will not get lost in even the densest forests. Second, their tracking ability means the god will bring in extra food when he hunts. Third, their archery can weaken enemies during the “skirmish” period before a fight, during which woodsmen, eagle fetches, and properly armed gods can attack, though when it comes to actual battle, they are somewhat weaker than churls. Woodsmen are also often helpful in events that involve finding or navigating a tricky path, hunting or following animals, or attacking a foe from afar.

Unfortunately, woodsmen are not as easy to come by as churls. Outside of occasional events (mostly in woods, anyway), they are found only in forest villages, which are often remote and take time to visit. And they demand gold for their hire. That cost is likely worth it, but as with everything in Fallen Gods, the player will need to make strategic and tactical judgments about the trade offs among resources.

Fighters

With a mighty howl, he hurls himself upon the gate with such a swing as should shudder the stones themselves. But it is the fighter himself who bears the brunt of the blow, burnt to ash before your eyes by the barrow’s wards. As his cinders smolder, you take your leave, having no wish to stake your life on this luckless bet.

Like churls, fighters are bland followers that lack special non-combat abilities and almost never open new paths in events. But unlike churls, they are of great help in battle. As noted, while the god is strong and good with a sword, he can be overwhelmed when outnumbered by foes. Many followers (churls, woodsmen, priests, maidens, and skalds) can stand in the way of enemy blows, but are unlikely to overcome serious threats and can fall relatively quickly. Not so for fighters. They are the classic Norse warriors, steadfast in the shield wall and deadly with their battle-axes.

Contrary to popular culture, not every Norseman was a skilled fighter, and in Fallen Gods, finding these men is not as easy as knocking at the first door. Good warriors tend to seek out the halls of lords who can dole out golden rings and other rewards. In our game, that means that they can be found in towns (ruled by thanes) or strongholds (ruled by jarls). They are also found in hillsteads, reflecting the raiding culture of those hardy folk. Enticing fighters to join means offering gold of your own, though there is no ongoing “upkeep” cost other than food. Certain events can also yield fighters as followers. While not as common as churls (who are, after all, commoners), they are not hard to come by.

Priests

Priests keep the craft of death as fighters the skill of killing, and your man shows himself steadfast in this ugly work. He lays the blackened bodies so that they seem at rest, then sets atop their flesh such leaves and roots as will make the smell less foul. Into each ear he sings a few soft words, and then he bids all four to find the hush that lies beyond the Singers’ reach. As he ends, a third son steps forth from the shrubs where he had hidden. He came home too late to die beside his kin, but hoped their killers might come again. Though he has had no such luck, he says perhaps his song set him on this path to meet a god, and he offers to go wherever this new road leads.

Priests are the opposite of fighters: they can be recruited only in a single location (shrines), but they join for free; they have little battle prowess, but significant use outside of combat; and in contrast to a warrior’s stoic attitude, their mindset is driven by a strict code of laws that they are quick to trot out as necessary.

As a historical matter, we know very little about the role of priests in pre-Christian Norse society because what little we hear of the pagan faith is filtered through the eyes of terrified victims, hostile converts, or confused travelers. Our priests are inspired by what we know of pagan goði, the monks who played such an integral role in bringing literacy and Christianity to the Norse, and the roving lawspeakers who helped settle disputes in Scandinavia. In Fallen Gods, they are those entrusted by Orm to teach men right from wrong (by Ormfolk standards, at any rate). While they freely share knowledge of the law, they are more tightfisted with other lore, such as how to read runes. And, like holy men in many cultures, they practice the healing arts.

For practical purposes, the last point means that priests can help recover HP more quickly than by resting (thus saving time) and can remove the “crippled” status ailment (which halves the strength of one so afflicted and thus reduces a fighter to less than the level of a churl in combat, and a churl to an utter weakling). Their broader range of knowledge shows itself in events, where they can offer up legal solutions to problems that would otherwise come to violence, figure out the meaning of ancient signs, and perform religious offices such as burial services.

Alas, as Henry II complained, a “turbulent priest” can make a leader’s life difficult. One reason a priest will join the god for free is to keep an eye on him. These followers are perpetually chiming in with advice on how the god should (or should not) handle a situation, and are equally eager to chide him if he does not follow this guidance. A priest whose advice is ignored will become increasingly unhappy until he simply leaves the god’s side, requiring the long journey back to a shrine if the god wishes to replace him. Moreover, priests are of little use in a fight (or a hunt), and their presence in the warband displaces other more practically helpful followers. Thus, despite being “free” to hire, they, too, have their costs.

Berserks

The two great men come to grips, both empty handed but each with strength enough to deal death with limbs alone. All about, the others watch, first with shouts and then with breathless awe as sinews swell and sweat gleams across the fighters’ skin. The raiders’ leader has never met a foe he had to fear, and he wrestles well. But your berserk has the bloodlust upon him, and he feels no blows or bites or butts as he wraps the other up in a crushing hug. The sea-reaver’s ribs crack, then his back snaps and he falls limp but still alive, until with a stamp your man stops his moaning. The winner raises his own hands high and roars his pride, while you take the food and gold stolen from the shorelands and send the raiders on their way. Your oarsmen beam with glee as they row on toward town.

The defanging of berserks (or “berserkers”) in modern depictions (whether in the X-Men or the Vikings) is a shame. The berserks of the sagas are not brooding anti-heroes whose violence, if excessive, erupts primarily against the wicked. Instead, they are at best brutes and bullies and at worst subhuman madmen who dress and behave like animals (for instance, by gnawing on their shields). To analogize to Marvel characters, they are more Carnage than Wolverine.

In this regard, it is telling that berserks are also called úlfhéðinn (“wolf-coats”). One of the worst legal punishments meted out in Norse cultures was to be declared outlaw (outside the protection of the law); an outlaw, like a wolf, was called a vargr. Wolves may today have various noble qualities to them but in darker ages they were banes of civilization, flock-destroyers and predators that might hunt anyone who strayed too far into the night or wilderness. Among the worst traits the sagas can ascribe to a man is “wolfishness.” And in the Völuspá, the world’s last gasp before it “goes down” is “a wind-age, a wolf-age.”

As noted, in Fallen Gods, the boundary between man and animal is particularly important because the old Firstborn gods, like the Great Wolf Amarok, are associated with beasts. Some, including Amarok, made a deliberate effort to degrade humans down to a bestial level. Wolf-men are Amarok’s men; their atavism is not just anti-social and against the law but unholy to boot.

But with this taboo comes immense power. Berserks are by far the mightiest and hardiest fighters in the warband. This helps not only in combat itself, but also during events, when they can assist the god by performing feats of strength. And on top of their striking power and health, they are immune to poison, sickness, and fear.

Of course, this very fearlessness means that they won’t retreat (such that if the player flees a fight, he loses any berserk followers) and can hardly restrain themselves when lying in wait. Further, they are contemptuous of a god who shows discretion, let alone cowardice, in the face of foes. If a berserk’s respect is lost, he will soon leave the warband altogether.

Thus, berserks are both hard to find—like witches, they can be enlisted only during events, never through ordinary recruitment—and hard to keep. And they tend to heighten the danger to the god even while helping him overcome it, for they may force fights the player would rather avoid.

Skalds

The skald sings of Fraener, wingless, grounded, put to another sort of flight, hunted and hounded across the land by Orm and his band, a ragged wanderer, sinking ever lower. Then comes the dragon’s hidden shame, how dread drove him to wear a man’s skin and live like a beggar among those he loathed. As he learns of his brother’s breaking, glee gleams in the wurm’s eyes: long has he lusted for Fraener to feel fear and fall far, to share the shame he showered on his kin. He pays for this pleasure with lore of his own, learned perhaps when he still lived among the clouds, or else dug up in his long days below the ground.

Fallen Gods owes much to the skalds whose well-wrought tales and sagas preserved the history and values of their people until the craft of writing could make a permanent record. Thus, although skalds play a relatively minimal role within the sagas (with the occasional exception such as Kormáks saga), I knew from the outset that they had to be in our game.

Our skalds are singers, tale-tellers, and keepers of cultural lore. This set of skills can be surprisingly useful: the world of Fallen Gods is full of powerful, unhappy beings who can be persuaded or pacified by a well-chosen allegory or aphorism. Even within the warband itself, skalds can use music and sagas to lift flagging spirits. Alas, these musicians are not warriors: they are among the weakest of combatants, incapable of dealing or withstanding much damage.

Skalds’ willingness to follow the fallen god arises from two impulses: their practical interest in being paid by powerful leaders for their flattery and their desire to witness deeds of derring-do in order to compose their own original works. The former means that a god must give some gold to enlist a skald (one can often be found at a stronghold, where they are playing second fiddle to the jarl’s court poet). The latter means that the god can keep his own skald happy by resolving events in ways that are well-suited to tale-spinning. Heroism is one useful trait in that regard, but skalds also enjoy irony and uncanniness.

Maidens

As the maiden gazes at her own fair face within the stone, her lips shape unspoken words and her eyes shine with tears. Whatever she sees holds her spellbound for a long span until, at last, she looks away and takes your hand, leading you through the maze while still lost in thought. To the end, she says nothing of what she saw.

The sagas are replete with canny, comely young women who inspire, ensnare, inflame, and otherwise wield influence over the men around them. This runs the gamut from the unnamed daughter of Halfdane in Beowulf (“a balm in bed to the battle-scarred Swede,” as rendered by Seamus Heaney) to the proud and scheming Hallgerður in Njal’s Saga, whose husbands wind up dead for their marital shortcomings. (No balm she.) While such women may not be “shield-maidens” in the vein of Hervor in The Saga of Hervor and Heidrek (Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks), neither are they passive bystanders in the sagas or our game. And though Norse myths and tales abound with female “prizes” chased and even traded by men—such as the Völsunga saga’s Brynhild (who, incidentally, is girded in what may be the first exploitative female fantasy armor: chain-mail “as tight as if it had grown to her skin”) to Freyja, pursued endlessly by gods, giants, and dwarfs throughout the Prose Edda—anyone familiar with these stories knows how well these women hold their own.

A major part of Fallen Gods is winning men and women to your side in your struggle to clamber back to the Cloudlands. While few mortals are a match for a god, having their help means that you will not need to fight your foes alone, and their skills may mean the difference between overcoming an obstacle and being stymied in your quest.

These “followers,” who together compose the god’s “warband,” are important thematically as well. While Norse sagas often focus on a single heroic figure, that hero is frequently defined by his relationship to his friends, family, and dependents. Thus, at the very outset, Beowulf’s skald tells us a young prince must “give[] freely while his father lives / so that afterwards in age when fighting starts / steadfast companions will stand beside him / and hold the line.” (Heaney Trans.) Interestingly, Beowulf ends with most of the king’s men running away from him, breaking the line, in his battle against the dragon. But even then, it is both thematically and tactically necessary for young Wiglaf to be there at his side to soften up the great dragon for Beowulf’s killing stroke.

There are sagas in which the protagonist is alone, but this is typically an abysmal and unusual situation—for instance, a consequence of being outlawed and cut off from human society, as in Grettir’s Saga or Egil’s Saga. The ordinary structure of these stories, reflecting the structure of the society from which they arose, is that a hero may outstrip other men and women, but he benefits from their wisdom, their rebukes, their shields, and ultimately their companionship. And from a narrative standpoint, they offer a chance for the hero to show his strengths and weaknesses in how he heeds or ignores that wisdom, bows to or refutes those rebukes, stirs or shakes the fighters who hold those shields, and wins or loses the hearts of those companions.

So too in Fallen Gods. Unlike many RPGs that make companions’ own goals, undertakings, personalities, and problems the focus of the narrative, Fallen Gods remains tightly focused on its titular protagonist. But unlike RPGs where companions are absolute non-entities, or where the hero has no companions at all, Fallen Gods uses followers as a means of enriching the god’s character and enhancing the player’s options. They will offer suggestions and reactions during events, and the player will be able to ask them to undertake tasks suited to their special skills. While followers do not have individual personalities, their sharply distinct classes (churls, woodsmen, fighters, priests, berserks, skalds, maidens, and witches) make them stand out from each other narratively, while also offering different strategic benefits at different costs.

Before going into detail about each class, it may be helpful to provide a framework for what kind of costs and benefits followers may present.

First, a follower must be located and persuaded to join the warband. Traveling to a location where the follower can be found (like a shrine or stronghold) can take days, and time is the player’s only irreplaceable resource. Once the player reaches the necessary location, the follower must be recruited. Some followers, like churls, will ask nothing; others, like fighters, will want gold; and yet others, like witches, will demand a much higher price.

Except for those that are “sworn,” a rare minority, followers must be kept happy or they will leave the warband. This requires feeding them every day; hunger eats the bonds of loyalty. Food costs either gold (if bought in town) or time (if gotten by hunting). The more followers you have (the warband can include up to five), the more food you need. Followers will also grow unhappy (and weakened) by status ailments such as being crippled (which halves might), cursed (which harms luck), or sick (which drains HP).

But even a healthy, well-fed follower will grow unhappy if the god errs. Few are fond of a god who flees or fails. And even success can be a matter of taste—the same wise restraint that impresses a priest may disgust a berserk, for instance. The player can gladden (and sometimes strengthen) a follower with the gift of an item, whether a lesser thing like a golden arm-ring or a great treasure such as Firebrand. But a gifted item is gone for good; the god can never get it back. Rest or a skald’s song can sometimes soothe the warband’s spirits, but the day thus lost cannot be regained, either.

Assuming the player can find and keep a warband, however, he gains an important edge inside and outside of combat. In battle, even a powerful god can be overwhelmed when faced with multiple foes. Followers are necessary to even the odds and prevent the god from being flanked or surrounded. And some followers, such as berserks, can do much more than merely soak up blows that would otherwise land upon the god: they can deal out death as well as their leader. Moreover, certain followers can help against certain types of foes (such as woodsmen against wolves) given their knowledge and skill.

Outside of battle, followers’ might and craft can provide the god with both generic benefits (such as the ability of a skald to raise morale, mentioned above) and special options inside of events. While events focus primarily on the god, his skills, and his choices, followers open paths in the choose-your-adventure-style events that otherwise would be unavailable—a maiden might be traded for a wurm’s wisdom; a witch might swindle dead men of their strength; a berserk might hoist a boulder too heavy for the god to lift; a priest might offer an old law to put a bitter feud to rest.

In these ways, assembling a warband is both fun in itself and a critical strategic layer of the game. The player’s job is to plot a path to victory and decide what costs can (and must) be borne to make that path possible. To be sure, luck and experience both have a role to play alongside pure reason, but there is no single combination necessary for victory: Fallen Gods is about exploration, and the dynamics and possibilities unlocked by different followers is one of the things the player is encouraged to explore.

With that framework in mind, and without further ado, here are the eight classes of followers in Fallen Gods.

Churls

To watch two churls bicker and barter over a barrow full of food is worth a laugh, but your man has a low cunning that shows itself fit for such work. In the end, he brings you much more food than you ever would have won for your gold. This is as good a deed as he can hope to do on behalf of a god, and he beams with pride when you nod in thanks.

Modern English reflects the scorn that aristocratic speakers had for those who work the land: “villain,” “churl,” “boor,” and other words that once simply meant farmer or herder are retained now in a purely pejorative sense. Notwithstanding Sir Walter Scott’s clever observation about post-1066 England in which Anglo-Saxon was the language of the field and French the language of the feast, it turns out that most of our words for one who works the land are French (like “farmer” or “peasant” or “villager”). “Yeoman” did not have a fieldworker meaning until late in its life, and is too positive for the role occupied by farmers in our setting. Hence, we are left with “churl” (from ceorl), a word that fits the low esteem the fallen god has for this class of follower.

Because churls are men who live by dint of their hard work in the fields, they are sturdy enough folk. But they lack the gear or training of a fighter, and the narrow horizons of a farmer’s life mean that they are prone to fears and superstitions. To some degree, this benefits the god: churls can be recruited for free because they are so flattered to have a god’s attention. Thus, for a player looking merely for followers to stand in the line and support the god in battle (with unskilled blows from wooden clubs), churls are a cheap and easy option. They can be found in any of the three types of steadings (plains, forest, hills) or in towns.

But beyond filling out the warband, churls don’t do much. They have no special skills, and thus are seldom helpful in opening new paths in events. In battle, they can stand and fight, but many foes will make short work of them. And while they will freely join, they eat just as much as any other follower and thus are not without their cost. A god who leads only churls may find some strength in numbers, but he is unlikely to win his way back home.

Woodsmen

Woodsmen are perhaps of even lower class than churls because they live on the outskirts of civilization, clad in skins, hunting and foraging like forest animals. In the world of Fallen Gods, there is deep fear of humans backsliding into a pre-civilized state, one associated with the Firstborn gods overthrown by Orm. Woodsmen are close enough to that line that, despite generally being decent and somewhat gentle beings, they are not wholly welcome outside of their own forest villages.

Nevertheless, they have several skills that make them highly desirable followers. First, their pathfinding ability ensures that a god with a woodsman in his warband will not get lost in even the densest forests. Second, their tracking ability means the god will bring in extra food when he hunts. Third, their archery can weaken enemies during the “skirmish” period before a fight, during which woodsmen, eagle fetches, and properly armed gods can attack, though when it comes to actual battle, they are somewhat weaker than churls. Woodsmen are also often helpful in events that involve finding or navigating a tricky path, hunting or following animals, or attacking a foe from afar.

Unfortunately, woodsmen are not as easy to come by as churls. Outside of occasional events (mostly in woods, anyway), they are found only in forest villages, which are often remote and take time to visit. And they demand gold for their hire. That cost is likely worth it, but as with everything in Fallen Gods, the player will need to make strategic and tactical judgments about the trade offs among resources.

Fighters

With a mighty howl, he hurls himself upon the gate with such a swing as should shudder the stones themselves. But it is the fighter himself who bears the brunt of the blow, burnt to ash before your eyes by the barrow’s wards. As his cinders smolder, you take your leave, having no wish to stake your life on this luckless bet.

Like churls, fighters are bland followers that lack special non-combat abilities and almost never open new paths in events. But unlike churls, they are of great help in battle. As noted, while the god is strong and good with a sword, he can be overwhelmed when outnumbered by foes. Many followers (churls, woodsmen, priests, maidens, and skalds) can stand in the way of enemy blows, but are unlikely to overcome serious threats and can fall relatively quickly. Not so for fighters. They are the classic Norse warriors, steadfast in the shield wall and deadly with their battle-axes.

Contrary to popular culture, not every Norseman was a skilled fighter, and in Fallen Gods, finding these men is not as easy as knocking at the first door. Good warriors tend to seek out the halls of lords who can dole out golden rings and other rewards. In our game, that means that they can be found in towns (ruled by thanes) or strongholds (ruled by jarls). They are also found in hillsteads, reflecting the raiding culture of those hardy folk. Enticing fighters to join means offering gold of your own, though there is no ongoing “upkeep” cost other than food. Certain events can also yield fighters as followers. While not as common as churls (who are, after all, commoners), they are not hard to come by.

Priests

Priests keep the craft of death as fighters the skill of killing, and your man shows himself steadfast in this ugly work. He lays the blackened bodies so that they seem at rest, then sets atop their flesh such leaves and roots as will make the smell less foul. Into each ear he sings a few soft words, and then he bids all four to find the hush that lies beyond the Singers’ reach. As he ends, a third son steps forth from the shrubs where he had hidden. He came home too late to die beside his kin, but hoped their killers might come again. Though he has had no such luck, he says perhaps his song set him on this path to meet a god, and he offers to go wherever this new road leads.

Priests are the opposite of fighters: they can be recruited only in a single location (shrines), but they join for free; they have little battle prowess, but significant use outside of combat; and in contrast to a warrior’s stoic attitude, their mindset is driven by a strict code of laws that they are quick to trot out as necessary.

As a historical matter, we know very little about the role of priests in pre-Christian Norse society because what little we hear of the pagan faith is filtered through the eyes of terrified victims, hostile converts, or confused travelers. Our priests are inspired by what we know of pagan goði, the monks who played such an integral role in bringing literacy and Christianity to the Norse, and the roving lawspeakers who helped settle disputes in Scandinavia. In Fallen Gods, they are those entrusted by Orm to teach men right from wrong (by Ormfolk standards, at any rate). While they freely share knowledge of the law, they are more tightfisted with other lore, such as how to read runes. And, like holy men in many cultures, they practice the healing arts.

For practical purposes, the last point means that priests can help recover HP more quickly than by resting (thus saving time) and can remove the “crippled” status ailment (which halves the strength of one so afflicted and thus reduces a fighter to less than the level of a churl in combat, and a churl to an utter weakling). Their broader range of knowledge shows itself in events, where they can offer up legal solutions to problems that would otherwise come to violence, figure out the meaning of ancient signs, and perform religious offices such as burial services.

Alas, as Henry II complained, a “turbulent priest” can make a leader’s life difficult. One reason a priest will join the god for free is to keep an eye on him. These followers are perpetually chiming in with advice on how the god should (or should not) handle a situation, and are equally eager to chide him if he does not follow this guidance. A priest whose advice is ignored will become increasingly unhappy until he simply leaves the god’s side, requiring the long journey back to a shrine if the god wishes to replace him. Moreover, priests are of little use in a fight (or a hunt), and their presence in the warband displaces other more practically helpful followers. Thus, despite being “free” to hire, they, too, have their costs.

Berserks

The two great men come to grips, both empty handed but each with strength enough to deal death with limbs alone. All about, the others watch, first with shouts and then with breathless awe as sinews swell and sweat gleams across the fighters’ skin. The raiders’ leader has never met a foe he had to fear, and he wrestles well. But your berserk has the bloodlust upon him, and he feels no blows or bites or butts as he wraps the other up in a crushing hug. The sea-reaver’s ribs crack, then his back snaps and he falls limp but still alive, until with a stamp your man stops his moaning. The winner raises his own hands high and roars his pride, while you take the food and gold stolen from the shorelands and send the raiders on their way. Your oarsmen beam with glee as they row on toward town.

The defanging of berserks (or “berserkers”) in modern depictions (whether in the X-Men or the Vikings) is a shame. The berserks of the sagas are not brooding anti-heroes whose violence, if excessive, erupts primarily against the wicked. Instead, they are at best brutes and bullies and at worst subhuman madmen who dress and behave like animals (for instance, by gnawing on their shields). To analogize to Marvel characters, they are more Carnage than Wolverine.

In this regard, it is telling that berserks are also called úlfhéðinn (“wolf-coats”). One of the worst legal punishments meted out in Norse cultures was to be declared outlaw (outside the protection of the law); an outlaw, like a wolf, was called a vargr. Wolves may today have various noble qualities to them but in darker ages they were banes of civilization, flock-destroyers and predators that might hunt anyone who strayed too far into the night or wilderness. Among the worst traits the sagas can ascribe to a man is “wolfishness.” And in the Völuspá, the world’s last gasp before it “goes down” is “a wind-age, a wolf-age.”

As noted, in Fallen Gods, the boundary between man and animal is particularly important because the old Firstborn gods, like the Great Wolf Amarok, are associated with beasts. Some, including Amarok, made a deliberate effort to degrade humans down to a bestial level. Wolf-men are Amarok’s men; their atavism is not just anti-social and against the law but unholy to boot.

But with this taboo comes immense power. Berserks are by far the mightiest and hardiest fighters in the warband. This helps not only in combat itself, but also during events, when they can assist the god by performing feats of strength. And on top of their striking power and health, they are immune to poison, sickness, and fear.

Of course, this very fearlessness means that they won’t retreat (such that if the player flees a fight, he loses any berserk followers) and can hardly restrain themselves when lying in wait. Further, they are contemptuous of a god who shows discretion, let alone cowardice, in the face of foes. If a berserk’s respect is lost, he will soon leave the warband altogether.

Thus, berserks are both hard to find—like witches, they can be enlisted only during events, never through ordinary recruitment—and hard to keep. And they tend to heighten the danger to the god even while helping him overcome it, for they may force fights the player would rather avoid.

Skalds

The skald sings of Fraener, wingless, grounded, put to another sort of flight, hunted and hounded across the land by Orm and his band, a ragged wanderer, sinking ever lower. Then comes the dragon’s hidden shame, how dread drove him to wear a man’s skin and live like a beggar among those he loathed. As he learns of his brother’s breaking, glee gleams in the wurm’s eyes: long has he lusted for Fraener to feel fear and fall far, to share the shame he showered on his kin. He pays for this pleasure with lore of his own, learned perhaps when he still lived among the clouds, or else dug up in his long days below the ground.

Fallen Gods owes much to the skalds whose well-wrought tales and sagas preserved the history and values of their people until the craft of writing could make a permanent record. Thus, although skalds play a relatively minimal role within the sagas (with the occasional exception such as Kormáks saga), I knew from the outset that they had to be in our game.

Our skalds are singers, tale-tellers, and keepers of cultural lore. This set of skills can be surprisingly useful: the world of Fallen Gods is full of powerful, unhappy beings who can be persuaded or pacified by a well-chosen allegory or aphorism. Even within the warband itself, skalds can use music and sagas to lift flagging spirits. Alas, these musicians are not warriors: they are among the weakest of combatants, incapable of dealing or withstanding much damage.

Skalds’ willingness to follow the fallen god arises from two impulses: their practical interest in being paid by powerful leaders for their flattery and their desire to witness deeds of derring-do in order to compose their own original works. The former means that a god must give some gold to enlist a skald (one can often be found at a stronghold, where they are playing second fiddle to the jarl’s court poet). The latter means that the god can keep his own skald happy by resolving events in ways that are well-suited to tale-spinning. Heroism is one useful trait in that regard, but skalds also enjoy irony and uncanniness.

Maidens

As the maiden gazes at her own fair face within the stone, her lips shape unspoken words and her eyes shine with tears. Whatever she sees holds her spellbound for a long span until, at last, she looks away and takes your hand, leading you through the maze while still lost in thought. To the end, she says nothing of what she saw.

The sagas are replete with canny, comely young women who inspire, ensnare, inflame, and otherwise wield influence over the men around them. This runs the gamut from the unnamed daughter of Halfdane in Beowulf (“a balm in bed to the battle-scarred Swede,” as rendered by Seamus Heaney) to the proud and scheming Hallgerður in Njal’s Saga, whose husbands wind up dead for their marital shortcomings. (No balm she.) While such women may not be “shield-maidens” in the vein of Hervor in The Saga of Hervor and Heidrek (Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks), neither are they passive bystanders in the sagas or our game. And though Norse myths and tales abound with female “prizes” chased and even traded by men—such as the Völsunga saga’s Brynhild (who, incidentally, is girded in what may be the first exploitative female fantasy armor: chain-mail “as tight as if it had grown to her skin”) to Freyja, pursued endlessly by gods, giants, and dwarfs throughout the Prose Edda—anyone familiar with these stories knows how well these women hold their own.

Thus, the maidens of Fallen Gods are by no means averse to cutting an enemy down with a dagger, though they are more likely to wield their wits or tongues as weapon. Typically, they are instigators rather than perpetrators of violence because they expect the god to be bold and not to shrink from danger, threats, or insults. Gods who fall short in this regard, or who show themselves greedy or petty, will have a hard time keeping a maiden from leaving.

While in the warband, maidens are not only able to help in fights but also in healing the god when he rests, as basic combat care is a common talent among the saga women who are invariably patching up both wounded men and tattered social fabric. They are also adept at spotting and exploiting the vanities of men, and monsters, that the god may encounter in events.

Witches

An unholy howling rouses you from your rest, and in the dark you spot a loathsome bulk astride the balking hermit. Hag-ridden, he cries for help, a call only half-heard with all the caterwauling. Before your mind can make head or tail of this unseemly tupping, the witch leans down and seems to suck the very sound, and life, from his lips. She turns to you and spits, muttering that she’s sprung you from a wizard’s trap. Striking a light, you see scattered tools and runes that do indeed bespeak black spells. You leave the dead man and his hut without waiting for the dawn.

Because witches were discussed extensively in a prior update, their character will be mentioned only in summary here: they are mighty, wicked beings devoted to upending the world’s orderly operation. Their interest in helping the god is perverse: they want him to return to the Cloudlands because the other gods want him out. They are most pleased with the god when he causes chaos, overthrows law, or shames the great.

All said, witches are likely the most powerful followers. Not only are they deadly in fights (albeit somewhat weaker than berserks or the best fighters), they have extremely useful skills outside of combat. Witches offer one of only three ways to lift curses (the god’s soulfire skill can do so at the cost of a soul, and the Skinbound book can do so at the cost of a day), a status ailment that causes the god to fail any luck roll and to suffer a penalty to all rolls. On top of this basic ability, witches open a host of interesting paths in events, using their unique abilities to overcome obstacles in surprising ways. Moreover, like the god, they can grow in power through the souls of others, but their use of souls is much darker than his—more akin to vampirism than worship. They particularly enjoy draining the strength from powerful men, like wizards, or from the young and beautiful, like maidens. Thus, they can grow even more powerful if the player permits them to indulge in such feasts.

But while witches can be very useful, their cruelty and perversity offends other followers. They thus cause persistent unhappiness and can completely destroy the warband’s morale when, say, eating a baby or defiling a shrine. The player is put in the difficult position of giving way to the witch’s unholy wants and alienating his other followers, or denying her wishes and driving her off. Because finding a witch is very difficult to begin with (often requiring a trek into the heart of a deep marsh or overcoming a tricky challenge) it may be hard to give her up once that high price is paid.

* * *

Winning in Fallen Gods, or even just exploring its maze of paths and uncovering its secrets, will require assembling the right warband for particular challenges ahead. Such strategy will involve a mix of common sense (e.g., adding a woodsman before exploring a vast forest), in-game information gathering (e.g., finding out about a cave before attempting to delve its depths), and specific experience (e.g., knowing from having encountered certain events before that a certain follower would be helpful). As the player learns about the game’s lore and rules, he’ll become better at that kind of strategizing.

But Fallen Gods is different from more punishing rogue-likes that require the perfect combination of tools (and luck) to win. Our focus is more on ensuring that every combination of followers (and god skills and items) yields new and interesting opportunities for the player to engage with the game and make satisfying choices. You may not win every time, but our hope is that some new path will open or some new wrinkle will be found on an old path, such as a priest’s forlorn commentary on a witch’s misdeed, or a berserk’s catastrophic rush to battle that spoils a well-laid ambush. By wrangling with this cast of characters, the god—and, more importantly, the player who controls the god—will be able to show himself as not only a hero but a leader, for better and worse.

NEXT UPDATE: Violence

* * *

I’ve previously mentioned King of Dragon Pass, a classic game with some similarities to Fallen Gods. Recently, the developer (A-Sharp) released a successor called Six Ages: Ride Like the Wind. In some ways it is the anti-Fallen Gods—progress is incremental, rather than chunky; there is no single player-character on whom the narrative and action is focused; the relationship between cause and effect is often opaque; choices often seem nuanced and subtle rather than bold and stark.

But in other ways, Six Ages may illuminate some aspects of how followers work in Fallen Gods; they play a similar role of providing advice and commentary during events, offering unique solutions to challenges, and giving passive and active bonuses for certain actions.

More importantly, Six Ages is one of the finest examples of a created mythology that I can think of (rivaling Tolkien’s famed work and certainly exceeding my own). It is not merely that the mythology is compelling; it’s that it feels real, the way mythology is at once very strange and deeply connected to our relationship with the world. And the way the player engages with the mythology directly (through ritual reenactments and retellings) and indirectly (by understanding the cultural implications of his actions in events) is unparalleled by anything I’ve seen other than King of Dragon Pass itself. In this regard, and others, it also captures the perils and pleasures of being a leader in a premodern society.

For now the game is only available on iPhone, with the attendant annoyances and benefits that brings, but it should come to computers next spring. I highly recommend it.

Thursday, July 12, 2018

Fallen Gods Update #6: Mappa Mundi

You walk in the gloom of old firs, lost in thought, the world still but for your shuffling steps, the low-growing rowan blown by the breeze, and far-off birds softly purling. When at last you shake loose from this wood-spell, you find the path long gone, and the day’s last span is spent in merely getting back.

Fallen Gods is a game focused on exploration. While that includes mechanical and narrative layers of exploration, the first and most basic layer is simply walking the land, seeking opportunity and avoiding danger.

The promise of a wonder-filled world to explore is one of the great pleasures of fantasy novels and RPGs. As civilized pleasures go, this one has a long pedigree: medieval maps purporting to depict the real world, such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi, look much closer to a Might & Magic map than what we would find in a contemporary atlas. In fact, even modern tourist maps retain some of this breathless excitement, a kind of simultaneous streamlining and exaggerating of the world to emphasize “points of interest” and tantalize the traveler with the adventure to be found at them.

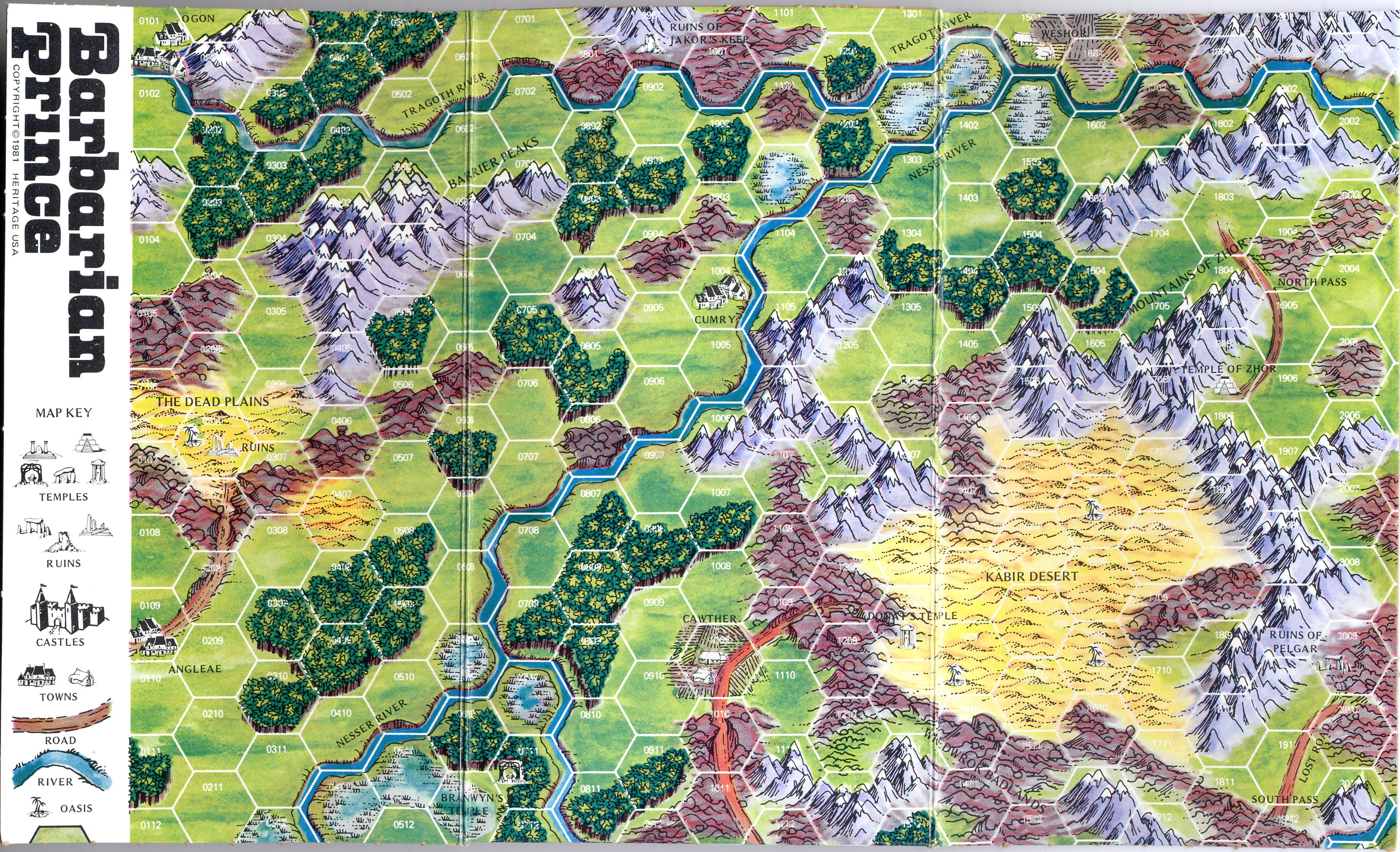

This “point of interest” concept is, literally, used to describe map features in RPGs and strategy games. As I discussed in the “Days of Yore” update, one of the key inspirations for Fallen Gods was the old board game Barbarian Prince, a single-player board game that used a large, hex-celled map. And you can see such “points of interest” here: the Ruins of Pelgar at the end of the Lost Road beyond the Kabir Desert; Branwyn’s Temple at the crook of the Nesser River; the town of Angleae that sits just south of the pass leading into the Dead Plains. Even a jaded and weary old timer like me still feels a certain tug of wanderlust when looking over that map.

Very early incarnations of Fallen Gods had a hex map (using some free-for-use tiles) that looked quite a bit like an uglier version of Barbarian Prince. But the addition of the wonderful Daniel Miller to the team meant that we could do better than that. And, as Arnold Hendricks himself discovered when making the jump from his board game to the cRPG Darklands, pixel art can create a more natural feel to the world: it looks like a land in which you’re adventuring, rather than a map over which you’re moving a token.

But while Darklands’ pixels furnish an attractive landscape that underscores the game’s well-researched realism, they seemed to lack a certain pizzazz when I first played the game. The reason, I think, is that I had spent formative childhood years playing console RPGs, and Chrono Trigger’s beautiful world maps had left a lasting impression on me.

So, with Fallen Gods, the impossible marching orders I gave Dan were to create hex tiles (which are useful for defining the game’s rules for world generation, movement, and the like) that fit together into a seamless pixel art world with distinctive points of interest. I’m pretty sure I used some word as unhelpful as “pizzazz,” perhaps with a wave of a hand. Dan, busy with his bowl of greasy phở (nothing but the best for our artists!), merely shrugged.

And then gave us this:

While this mock-up has a somewhat higher density of “points of interest” than you would see in the actual game, it is nevertheless fairly close to the real thing. In the actual game, points of interest fall into four general categories: (1) dwellings (steadings, towns, strongholds, and shrines); (2) dungeons (caves, marshes, and barrows); (3) locations; and (4) encounters.

Steadings—“villages,” if the word weren’t impermissibly French—are the lowest tier of civilization in Fallen Gods. They can be found on the plains (most commonly), in woods, or up in the hills. They are a fine place to recruit the lowest tier of follower, churls, who—overawed by the presence of a god and eager to escape a life of drudgery—will follow for free. In woodsteads, you can also find woodsmen (who are good guides and hunters, and whose archery can give you an edge in pre-combat skirmishing), and in hillsteads, where raiding is commonplace, you can find the occasional fighter. The lore steadings offer is mostly local gossip (i.e., information about nearby points of interest) and the quests tend to revolve around local issues such as feuds, food shortages, wolf problems, and the like. Since all steadings are centered around food gathering (farming, hunting, and grazing), food is usually inexpensive. And since the local headman is a petty leader, the obligatory guest-gift to rest in his hall is relatively light.

Towns, always located on either coasts or riverbanks, are hubs of trade and commerce. Churls still make up most of the population, but there are also mercenary fighters to be hired. Food is more expensive than in steadings (given the greater demand and proportionally smaller supply), as is rest, befitting the greater stature of a town’s thane. The lore tends to be broader—reflecting the wide-roaming nature of the town’s long ships—and the quests are directed seaward, dealing with plagues or visitors from abroad, river monsters or beached whales. A unique aspect of towns is that you can hire a ship to take you to any other town on the map, a quick way to travel in a game where time is the one resource that can’t be regained.

Strongholds are the seats of power for jarls, the highest-ranking leaders in a world where Orm has insisted on keeping his kingship even after becoming a god. Fighters are plentiful, and the god can also hire a skald here. The jarl’s own skald provides a rich source of lore, including not merely about what is going on in the land but about where legendary treasures and foes may be found. Stronghold quests reflect the intriguing that goes on around the powerful, particularly regarding matters of succession.

Shrines are dedicated to the worship of Orm and the Ormfolk, and are thus a welcome haven for the fallen god. The priests who tend the shrine and its holy fire will, for a suitable offering to their principal god Orm, provide magnificent healing services to any who rest within their temple. And if the god has no priest following him, the shrine will gladly provide one, to advise him on the laws of gods and men and to provide healing on the road. As for information, shrines’ loremasters know more than anyone, and thus a god can learn much about lost relics and the like. Finally, quests in shrines tend to be about questions of doctrine, performance of rituals, resolution of schisms, and similar theological issues.

Barrows—the characteristic above-ground burial mounds of the Norse—are the smallest dungeons, and indeed they are almost always only one “card” deep. There are many barrows on the map. A few contain nothing, a few contain minimal threats and rewards, and a few contain more significant adversaries. In general, barrows naturally feature the dead (draugar in Fallen Gods’ parlance), though one may also meet cavewights, outlaws, wizards, and wurms.

Caves can be of varying depth (from three to seven events down) and are full of subterranean foes: wolves making dens in the upper levels, trolls and trollshards seeking shelter from the sun, and cavewights and dwergs for whom these depths are home. Some dead from times long past may be interred in the depths, and wurms and other ancient evils can likewise be found at the bottom.

There is a single marsh dungeon on the map, and it is the largest dungeon, befitting the wending swamp paths. The waters are full of the unhallowed dead left behind in the Overthrow, as well as bogwights and worse. At the heart of a marsh a god may find a rotting Firstborn god, an encampment of dead men still fighting the old wars, a wise witch, or a wurm who thinks himself a king. Thematically, if caves are about the dark unknown and the preservation of the past, swamps are about filth and the decay of the present.

While the player can see the entire map when the game begins, locations are shown in a way that makes their nature somewhat non-obvious. When the god draws near, the location resolves into a clearer state. For instance, what initially appeared to be large boulders may turn out to be dead trolls. A tall pole may turn out to be the binding place of an outlawed berserk or a scorn pole with a horse’s head atop it.

The map will include many features like boulders or cairns or farm houses that are not location events; as the player draws near, they will not resolve into anything more interesting, and entering the hex will not cause an event to trigger. Thus, while the player may have some guesses about where he can go, he won’t know for sure that a map feature is a location event until he either investigates it, gathers lore about it in a dwelling, or uses the Foresight skill (at the cost of a soul) to scry it out from a distance. Bird fetches (ravens or eagles) have the benefit of expanding the god’s range of investigation, such that he can discern location events from a greater distance than a god with a wolf or fox fetch.

Finally, encounters are transient events. They spawn as the god explores the world, appearing at the edge of his range of exploration. If he does not investigate quickly, the encounter disappears for good. An encounter might involve a churl bringing his harvest to market, a songspeaker hastening down the road on his unholy horse, or a pair of outlaws splitting the fruits of a murder. While other points of interest help make the world feel like more than empty space, encounters help bring it to life by suggesting that things happen on their own, and resolve on their own, rather than waiting in abeyance until the god deigns to intervene. Moreover, because they spawn near the god, encounters ensure that there is always something interesting to do, even when doubling back across ground you’ve already covered.

NEXT UPDATE: Followers

Fallen Gods is a game focused on exploration. While that includes mechanical and narrative layers of exploration, the first and most basic layer is simply walking the land, seeking opportunity and avoiding danger.

The promise of a wonder-filled world to explore is one of the great pleasures of fantasy novels and RPGs. As civilized pleasures go, this one has a long pedigree: medieval maps purporting to depict the real world, such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi, look much closer to a Might & Magic map than what we would find in a contemporary atlas. In fact, even modern tourist maps retain some of this breathless excitement, a kind of simultaneous streamlining and exaggerating of the world to emphasize “points of interest” and tantalize the traveler with the adventure to be found at them.

This “point of interest” concept is, literally, used to describe map features in RPGs and strategy games. As I discussed in the “Days of Yore” update, one of the key inspirations for Fallen Gods was the old board game Barbarian Prince, a single-player board game that used a large, hex-celled map. And you can see such “points of interest” here: the Ruins of Pelgar at the end of the Lost Road beyond the Kabir Desert; Branwyn’s Temple at the crook of the Nesser River; the town of Angleae that sits just south of the pass leading into the Dead Plains. Even a jaded and weary old timer like me still feels a certain tug of wanderlust when looking over that map.

Very early incarnations of Fallen Gods had a hex map (using some free-for-use tiles) that looked quite a bit like an uglier version of Barbarian Prince. But the addition of the wonderful Daniel Miller to the team meant that we could do better than that. And, as Arnold Hendricks himself discovered when making the jump from his board game to the cRPG Darklands, pixel art can create a more natural feel to the world: it looks like a land in which you’re adventuring, rather than a map over which you’re moving a token.

But while Darklands’ pixels furnish an attractive landscape that underscores the game’s well-researched realism, they seemed to lack a certain pizzazz when I first played the game. The reason, I think, is that I had spent formative childhood years playing console RPGs, and Chrono Trigger’s beautiful world maps had left a lasting impression on me.